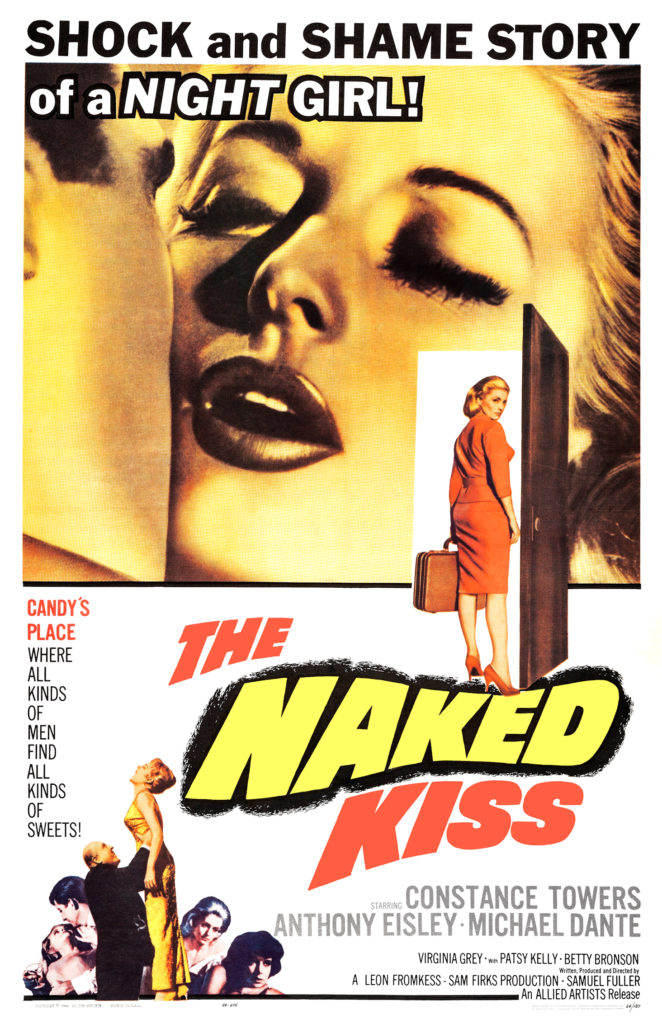

This was written as the introduction for the Mesilla Valley Film Society’s screening of The Naked Kiss in April, 2024.

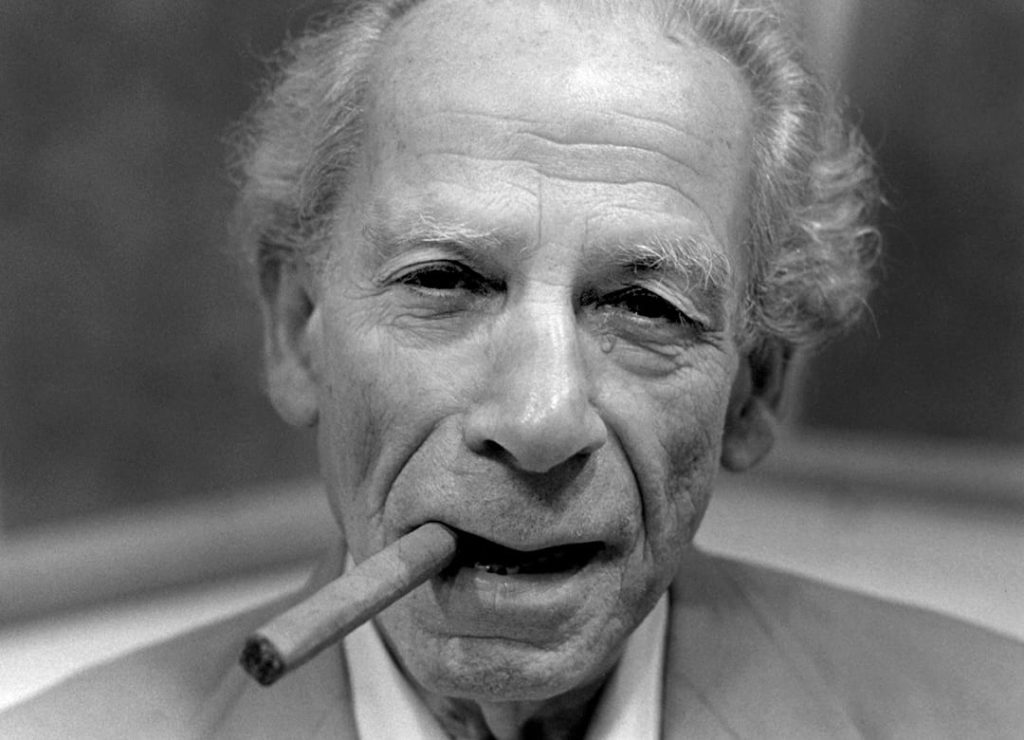

I don’t know if there’s an American filmmaker whose work I admire more than Sam Fuller.

A high school dropout who became a journalist, then a screenwriter, then a soldier in World War II before directing his first film, I Shot Jesse James in 1949. That movie was a revisionist western before those were even a thing, the story of John Ireland’s Bob Ford grappling with his titular legacy. From there, Fuller quickly became a b-movie staple, cranking out war pictures and period pieces before the critical and box office success of the noir classic Pickup on South Street gave him a chance to direct some headliners at Fox like the submarine flick Hell and High Water and the western Forty Guns.

Around 1959, though, he started losing some of his luster, with The Crimson Kimono leaving audiences and critics both a bit cool and Verboten! underperforming despite raves.1The Crimson Kimono, by the way, is one of my favorite films by him. A procedural that treats its parallel plot of interracial romance with a frankness Hollywood still rarely manages, a full half century later. Crime flick Underworld U.S.A. saw him butting heads with producers at Columbia and 1962’s Merrill’s Marauders was his final big studio picture for almost a decade.

Others would be daunted by this turn of events, but for Fuller, the need to create was stronger than the need for recognition. He went back to his b-picture roots with 1963’s Shock Corridor — a psychological thriller about a journalist who goes undercover in a mental institution — and made what I consider to be his most visceral, gutsy movie with tonight’s selection, The Naked Kiss.

In The Naked Kiss, Constance Towers plays Kelly, an itinerant prostitute who uses the guise of a champagne seller to meet and engage with her clientele. When she arrives in Grantville, though, she does her usual bit and meets with the local constabulary to smooth things out. However, Captain Griff2No first name given, nor last, just he’s just Griff. Griff is a recurring name in Fuller’s filmography, a tribute to a man he served with in WWII. It’s also the name we gave one of our dogs. makes it clear after their liaison; her services are not welcome in his town. She can ply her trade over the river, at Candy’s.

With a head full of champagne, Kelly wakes up the next morning and has a realization: she wants more from life. And she works hard and gets it…or so she thinks. Despite offering up what appears to be the idyllic American town (especially if you’re a white person in the 1960s), Grantville’s got a dark secret, one that’s likely to make your stomach turn, even a full sixty years after the film’s release.

If you can’t tell by the fact that I have a tattoo featuring David Lynch and a quote from the series, I’m a big fan of Twin Peaks. Like Fuller, Lynch and collaborator Mark Frost engaged with the American Dream and its darker side and there are some plot parallels that a fan of both the movie and the TV series can pick out, but what stands out to me the most is how both The Naked Kiss and Twin Peaks are steadfastly weird.

There’s a sequence in which Kelly sings along with some kids from the local hospital that’s as sincere as it is surreal. The brothel across the river uses the kid-friendly facade of a sweets shop to allow the women to meet their clients. The prostitute quotes Goethe and Byron with a familiarity that belies her past. With one exception, not a single character has an entire name in the movie. And it works, it all works.

Fuller (with cinematographer Stanley Cortez) is a pretty primitive filmmaker. In fact, outside of the bravura opening and the occasional long-ish take, there’s not much to distinguish the vast majority of his shots from what was on TV at the time. However, there’s a raw energy there, a sense of intent lacking in many of his peers that is undeniable, and it’s easy to see why the French New Wave and people like Jim Jarmusch, Martin Scorsese and John Cassavetes all fell so hard for the director. I hope you join them tonight.

Leave a Reply